As if stuck in a partially clogged drain, oil from the hottest U.S. shale play has been caught in a bottleneck due to a lack of pipeline capacity.

But the transportation tie-up at the Permian Basin is about to ease up, and a new network of pipelines will help U.S. producers unleash more crude into the Gulf Coast and then onto the world market.

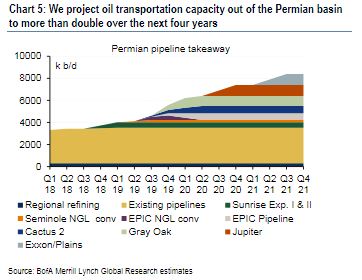

“There’s a lot of shale capacity being prepared. There’s a lot of pipeline capacity. We’re going to triple pipelines going into the market from 3 to 9 million in three years, from last year to late 2021,” said Francisco Blanch, head of commodities and derivatives at Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

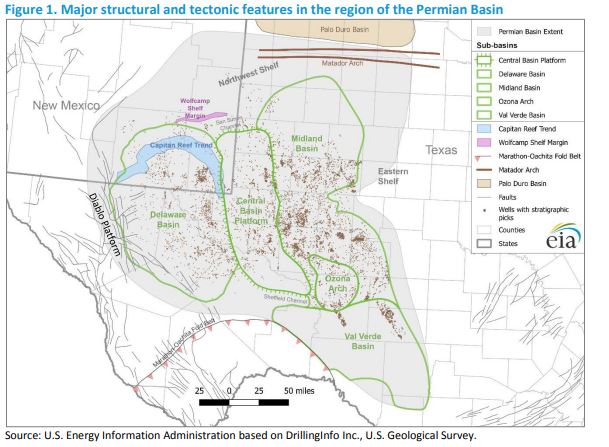

Much needed pipeline capacity is being added to take Permian crude from the heart of Texas down to the Gulf Coast, to oil refineries but also to Texas ports that are making plans for more and larger ships to carry oil exports from the U.S. to customers in Asia and elsewhere. The Permian Basin covers an area of more than 75,000 square miles in western Texas and southeastern New Mexico.

Citigroup energy analyst Eric Lee said Permian output at just under 4 million barrels a day is up about 1 million barrels from a year ago and should be a million more, or 5 million a day, a year from now, in early 2020. The Permian has benefited from consistent improvements in technology, which increasingly have been capable of extracting more oil from the shale formation.

“We’re happy to look out to 2023, when it gets to 8 million. … They figured out how to access it at very low break-evens, like $30/$40. … There are more layers below it. It’s hard to know what those are going to mean, break-even-wise,” said Lee. His estimates depend on the price of crude and world oil demand. Breakeven is the price a producer of a barrel of oil needs to recover expenses, or where a producer breaks even.

As Permian and other production has grown, so have U.S. exports of crude, allowed by a change in law in late 2015. In one week in the past month, exports reached a record 3.6 million barrels a day, according to U.S. government data. Last week, 2.8 million barrels a day were exported, and the four-week average was about 3 million barrels. The U.S. is now the largest oil producer in the world, pumping 12.1 million barrels a day, according to Energy Information Administration data.

Source: Bank of America Merrill Lynch

“Every incremental barrel that the United States produces will be exported. We’re in a situation, of course, where the quality of what we produce is actually higher than what we need,” said Raoul LeBlanc, vice president, North American Unconventional at IHS Markit. “U.S. refineries, which turn crude oil into the products we use, were designed to turn cheap crude oil into high quality and upgrade it into the fuels we use.”

The Permian and other U.S. shale basins produce light sweet crude, while the Gulf Coast refineries were built for heavy crudes, like those from Saudi Arabia, Venezuela and Mexico. With Venezuela under sanctions, there is less available heavy crude, but analysts say so far the refineries are able to find enough but at a higher price differential.

“We like to say we’re exporting champagne and importing beer,” said LeBlanc. The U.S., in the past week, imported 7 million barrels a day. Twice in the past several months, weekly data showed the U.S. to be a net exporter of crude and refined products.

“The growth estimates [for the Permian] just kept getting bigger and bigger. They didn’t’ know what they didn’t know,” said CFRA energy equity analyst Stewart Glickman. “You do have to be cognizant of the fact that these wells decline very quickly. Between year one and year two there’s a pretty big dropoff. You have to drill more well in order to expand. It really depends on whether technological innovations can keep pace with that. For everyone to double in five years might be a stretch. I’m not saying it can’t be done,” Glickman said.

U.S. crude in the Permian is increasingly being drilled by the oil majors.

“This is sort of typical for the industry. You start with wildcatters, then the smaller E and Ps move in. Then the big guys move in. We’re seeing it again here. it’s kind of like a neighborhood gets gentrified by the artists before the mainstream moves in,” Glickman said.

This past week, both Chevron and Exxon announced plans to bump up production significantly in the Permian. Occidental Petroleum and British Petroleum are also active there.

“They are doing these big integrated projects that are not that price sensitive,” Lee said. “If they okay a project, it’s going to move like a big project, more than a small to mid-cap producer, which are drilling fewer wells and are more sensitive to price.” He said smaller and mid-cap companies are also being impacted by capital discipline.

Exxon said it hoped to reach 1 million barrels per day of oil equivalents in five years, and Chevron said it expects to more than double its output, taking production to 900,000 oil equivalent barrels by the end of 2023.

“The big thing that I think has changed is the shale game has become a scale game, and so people that can do things at large scale and bring the capabilities to bear that a company like Chevron has are the ones that really can take this to the next level,” Chevron Chairman and CEO Michael Wirth told CNBC’s“Closing Bell” Tuesday.

As for the Permian bottleneck, Chevron said it has had more than sufficient takeaway capacity and primarily relies on pipelines, but also a few trucks. “Our offtake strategy allows us to keep up with our production,” the company said in a statement. “In 2018, we had takeaway capacity for oil and liquids that was more than sufficient, and we have already added more capacity this year.”

Lee said the expansion of pipelines to the point where they will now provide surplus capacity is typical of the industry. “Once you get to the first quarter of 2020, almost certainly the Permian will be fully de-bottlenecked for now,” he said.

The majors may be more impactful in terms of making sure there is plenty of pipeline space available.

“They’re going to plan not to have bottlenecks. … The bottlenecks are more a function of just the short term, mini boom- busts we’ve seen since the 2014 oil price crash,” Lee said.

In periods of higher oil prices, the focus turns to building pipelines, and if prices fall pipeline space becomes more plentiful. “Oil prices have been recovering. The pipelines are now catching up. They slowed down after being overpiped,” Lee said, adding that there is currently more capacity coming on ahead of the expected increase in production.

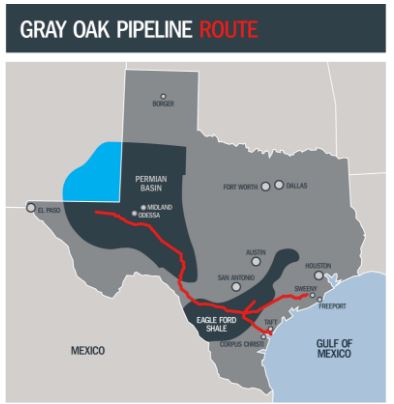

Glickman said the Gray Oak pipeline is adding 800,000 barrels a day; Epic is adding 600,000 and another named Cactus 2, owned by Plains All American, is adding another 600,000 barrels a day. The Gray Oak, built and operated by Phillips 66, is an 850-mile pipeline stretching from south of Midland down to Corpus Christi.

“Those are just the ones coming on line late this year. That’s a lot of volume,” he said.

Oil in Midland, Texas, the center of the Permian, is priced lower than crude at the Gulf Coast, and the differential has been about $10 per barrel or more. West Texas Intermediate crude is just above $56 per barrel.

“They realized prices they were getting for Permian were getting weak. The installation of new pipelines should boost realized prices, if you are a Permian producer. If you have a choked highway and someone adds a couple lanes to the freeway, you’re eventually going to encourage more drivers,” Glickman said.

John Kilduff, partner with Again Capital, said the production plans could create a temporary glut. “But with all the new projects being lined up, liked the push by Exxon Mobil and Chevron, there will still be a battle for pipeline space in the future,” said Kilduff.

Photo: Oil operations in the Permian Basin near Midland, TexasNick Oxford | Reuters — As published at CNBC