Mike Christensen strides among rows of gleaming steel tanks, pointing to pipelines that arrive from miles around to this corner of former farmland near Midland, Texas, the heart of the largest oil patch in the United States.

His company is one of dozens opening sites like this one that handles, not the lucrative oil, but the shale industry’s dirty secret: wastewater.

While U.S. oil production has reached record levels on account of the shale revolution of the last decade, much of the supporting infrastructure has failed to keep up, including how to transport the large quantities of water used in the hydraulic fracturing process and the water that is produced from wells alongside oil and gas.

Once managed individually by energy producers, the job of supplying, collecting and disposing of water is a rising cost, and has spawned a $34 billion a year business in the U.S. that has lured investors including TPG Capital, Blackstone Energy Partners LP and Ares Management Corp to back these firms.

Oil production in the Permian basin that spans West Texas and southeastern New Mexico is expected to rise to rise 35 percent to 5.4 million barrels of per day (bpd) by 2023, requiring even more water supply and disposal, said analysts. In two New Mexico counties, firms produced 505 million barrels of oil from 2016-2018, and five times that in water, a Reuters analysis of state production data showed.

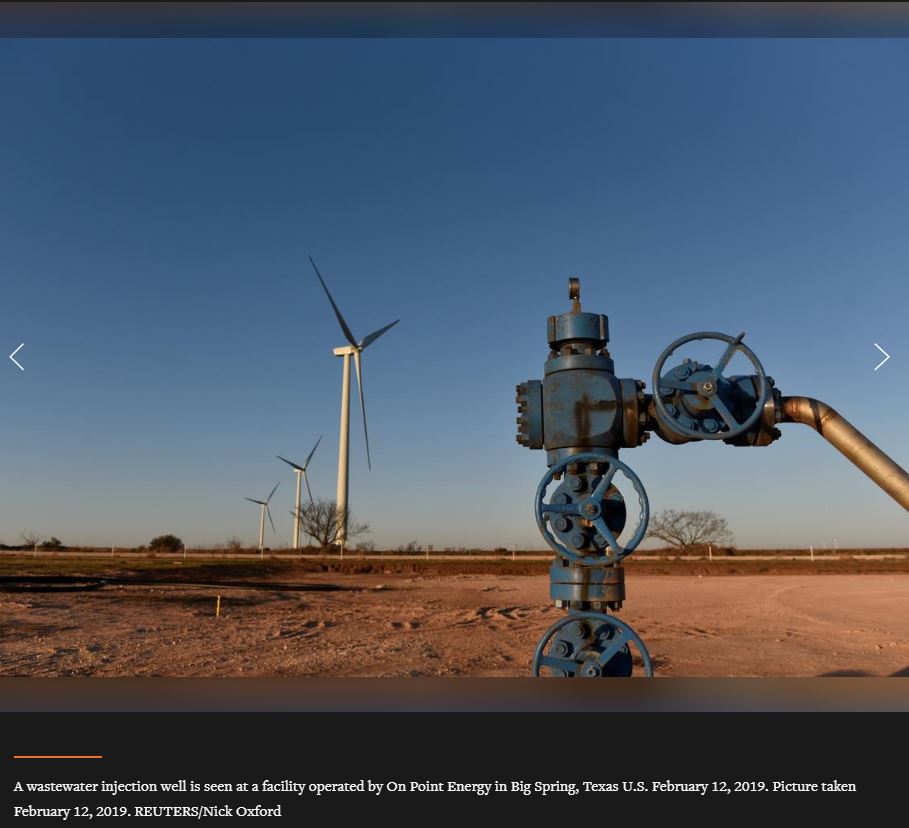

Photo:

A wastewater injection well is seen at a facility operated by On Point Energy in Big Spring, Texas U.S. February 12, 2019. Picture taken February 12, 2019. REUTERS/Nick Oxford