There is a buzz in the gas market, the likes of which has not been seen for a number of years. In the space of a year, we have moved from an expectation of plentiful cheap supplies to a concern that shortages could emerge if we have a cold winter. The journey to this new reality was somewhat predictable as several key factors including lack of drilling, under-investment in new sources of supply, capital restraint on the part of producers, and a shift toward renewable energy capital allocation have been in play for over a year now. I discussed some of these factors in an earlier OilPrice article back in June and forecast that prices would likely continue to rise for both oil and gas. Prices for both are higher now, but as we have seen, gas has continued to outperform oil in a year-over-year tripling of prices.

Recently some additional factors have entered the equation or sharpened their focus, and have contributed to the new scarcity mindset I mentioned above. In this article, we will review how these new factors have exacerbated the overall market, what we see happening over the near term, and what could influence the final trend that gas takes in the next nine months to a year.

Europe and the UK pay a price for energy “Greening”

One factor is the “greening” of the energy supply around the world, particularly in Europe. Much of the current global environmental impetus culminating in the thinking of Co2 as a harmful gas has its origins on the Continent and has easily spilled over the Channel to the U.K. Over the last decade, European countries have shifted to wind and solar for electricity generation, in pursuit of Paris goals and NetZero carbon in 2050. They have paid a price for this greenness ass you can see in the chart below. By comparison, in much of the U.S. utility rates average around $0.13 per KWH.

As a recent Wall Street Journal-WSJ article noted, this strategy is appearing a little fraught as over the summer months the wind stopped blowing, creating extra demand on what little gas supplies they had.

“The episode underscored the precarious state the region’s energy markets face heading into the long European winter. The electricity price shock was most acute in the U.K., which has leaned on wind farms to eradicate net carbon emissions by 2050. Prices for carbon credits, which electricity producers need to burn fossil fuels, are at records, too.”

Related: China Oil Consumption Seen Peaking In 5 YearsAdditionally, the Europeans disincentivized the production of gas through the introduction of carbon taxes for years. There is an old saying in economics, that if you want less of something, you tax it. So far, the veracity of that old maxim has been borne out, judging from supplies.

As so often is the case, some wounds are self-inflicted. In the case of gas, lower quantities of a key source of natural gas supply in Europe with the early closure of the Dutch gas giant, Groningen, helped bring the EU to the point they are at now. You can see imports from all sources track higher beginning in 2014 as supplies from Groningen began to be curtailed, and then were lowered still further in 2019.

The Rystad article notes the following prognosis as regards the European gas market, in relation to the Groningen curtailments.

“The drastic drop in output from Groningen will redefine the European energy landscape. The field, which had a rebound in production at the start of this century, reaching 57 billion m3 in 2013, was for decades the central cog in northwest Europe’s gas system.”

“The phase-out of this giant field will force Europe to expand its gas imports at an even quicker pace. We can already see this drastic shift taking place in the Netherlands, which is in the midst of the transition from being a net gas exporter to a net importer,” says Carlos Torres-Diaz, head of gas markets research at Rystad Energy.”

If you don’t keep up on happenings in Holland, decades of heavy withdrawals from Groningen had led to subsidence in the surrounding areas (always a concern for the Dutch.), and localized earthquakes of some severity. Plus, in the Dutch mindset, windmills are just a part of life.

When you combine the disincentives for drilling new supplies with the shift in capital allocations by producers as a result, you arrive where Europe is now. Having to pay out the nose to keep the lights and the heat on.

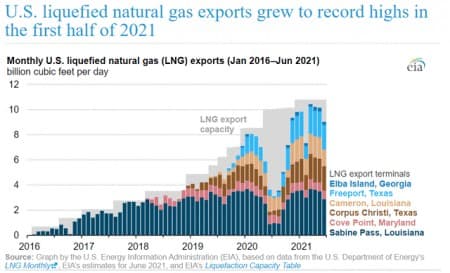

And, whom are they paying? The U.S.A. figures prominently in their energy mix. Shipments of LNG from U.S. shores to Europe had been running at all-time highs recently, and as this JPT article notes, we are still their biggest supplier, but the tide has shifted. Starting in 2020 Asia began to outbid European buyers for American supplies of LNG.

The Russians are coming to the rescue. At least right now. The EU depends on Russian gas to keep the lights on to an extent greater than suits their comfort, as the linked Bloomberg article notes. A recent Fortune article noted the eastward pull of Asia for gas supplies-

“Making things worse, Asia is still a center of LNG demand – and a growing one: a push by the Chinese government away from coal, paired with the general economic resurgence, is drawing gas from both the U.S. and Russia, while inventories are low globally ahead of winter.”

So with Russian inventories low, some are concerned that they want to make a political statement to Germany about Nordstream II, and with the pull of Asia for U.S. supplies, what’s the U.K and EU to do?

Without perhaps, as the recent fertilizer factory idling in the U.K presages.

Lost in the climate debate is the subject of fertilizer. Gas is used to make ammonia which in turn is used to make nitrate fertilizers. If you want to grow crops with maximum yields, or just grow them at all, you need fertilizer. And, no-there is no workaround to this century-old process known as the Haber-Bosch process, which removes hydrogen from methane – the principal component of natural gas. You can’t plug a wind farm into a cornfield and grow corn. You must apply fertilizer. And, to get that…you need gas.

Last week two fertilizer factories in the UK shut down because of high gas prices. When they will restart is anybody’s guess. As is the knock-on effect on fertilizer prices. As could become food prices which have been soaring for a variety of reasons.

When we combine all of these factors and add in one final variable – the chilly forecast for the winter in Europe, we have a troubling situation in the EU and UK for the next six to nine months.

Is the situation any better in the USA?

It will probably come as no surprise that the challenges we face in the U.S. are related to or similar to the problems across the pond. The EIA weekly gas storage report shows some modest improvement – up 83 BCF, from the week before, but reveals we are still about 8% below the 5-year average as we head into the winter withdrawal season.

At the same time, our supplies are curtailed from either a fall-off in shale drilling or a shut-in due to weather events, such as we experienced in the February Snowmaggedon event or the hurricanes that shut in GoM wells in August. We lost about 2-BCF/D from the GoM during this period, and some of it still had not been restored as of the second week in September.Related: Europe’s Energy Crisis Is Driving Up Natural Gas Prices Worldwide

Exports are consuming a larger share of our production than ever before in the form of LNG, and pipeline gas to Mexico. As we discussed above, the EU is increasingly dependent on supplies from the U.S. and Russia. In the case of the U.S., these supplies come in the form of LNG as it is easily transported by ship.

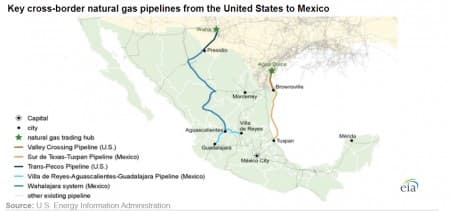

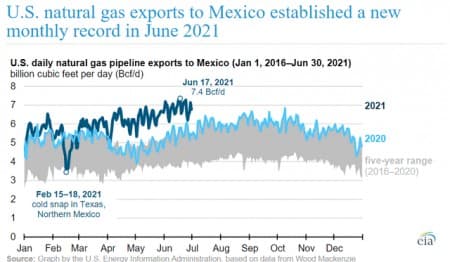

By increasing its pipeline infrastructure, Mexico has made a strategic decision to use more gas from its northern neighbor. A direct connection to the WAHA and Agua Dulce hubs has enabled the flow of billions of cubic feet per day southward. The linked Energy Information Agency article notes the volume of this flow of shale gas toward Mexico.

“U.S. natural gas pipeline exports to Mexico averaged 6.8 Bcf/d in June 2021, up 25% from June 2020 and 44% more than the previous five-year (2016–2020) monthly average. We expect these record-high flows, which were driven by increased power demand, high temperatures, and greater industrial demand in June, to continue through the summer.”

All of this gas is held by long-term contracts executed when supplies of gas were more plentiful, just a year ago.

Your takeaway

Shortages or tight supplies of gas could likely persist well into next year. The problems in Europe are structural. They are compelled to import gas from either the U.S. or Russia. Or both. Asia has set itself on a course that includes gas from these sources as well.

I think the same case can be made for the U.S. We have some of the same disincentives to drill for new supplies, governmental disfavor at the state and federal levels combined with challenges in obtaining financing. Many of the financial challenges have been abated by the increased cash flow being generated by drillers, but as we have seen they have little interest in growing supplies. This trend in shale drillers was noted in detail in an OilPrice article this month.

Outlier concerns could exacerbate this situation. We face a very antagonistic administration that is looking for ways to advantage renewables by punishing oil and gas. One feature is contained in the “Methane Reduction Act” which will levy what amounts to a carbon tax of $1,800 per ton on high carbon content fuels like natural gas which is mostly methane. Not satisfied with that, progressives are trying to disincentive the use of natural gas as a bridge fuel in their “Clean Electricity Program.” This punishes natural gas still further while providing payments for “clean sources.” Neither of these policies is certain to become law as states that would be harmed economically are fighting them. But the fact that they are being seriously discussed represents a change in the conversation.

Something that has to be rattling around in Progressive minds is a Wind Fall Profits Tax (WPT) on producers of oil and gas. This would be a resurgence of a Carter-era tax policy that sought to redistribute wealth through an excise tax on “unearned gains due to market conditions.” Sort of like the situation that now exists, where tight supplies of products against strong demand are driving up prices resulting in big increases in cash flows to oil and gas companies. The WPT was a horrible policy that failed to meet its objectives and created all sorts of adverse knock-on effects. It was repealed in 1988 to everyone’s great relief at the time. Wait for it to come around again, enough time has gone by that memories may have faded. That said, there are enough rational members of Congress who remember the lessons of the past, and whose constituencies would be harmed, that I don’t believe this notion will grow legs and walk.

In summary, the energy picture surrounding gas has changed over the last year. Supplies are tight, and producers are reluctant to allocate new capital to drilling. The result will be higher prices for the foreseeable future in the U.S. and in Europe. The real challenge will be meeting demand regardless of price.

Read it from OilPrice