America’s fastest-growing source of energy has a power problem.

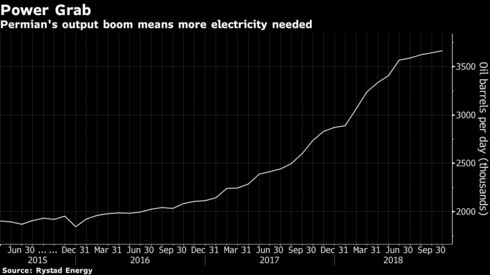

The Permian Basin, which produces almost 4 million barrels of oil a day, has expanded so quickly that suppliers of the electricity needed to keep wells running are struggling to keep up. The Delaware portion alone consumed the equivalent of 350 megawatts this summer, tripling the load from 2015. That’s enough to power about 280,000 U.S. homes. And providers say the draw is likely to triple again by 2022.

While providers are rushing to build new power lines, it takes three to six years to get them up and working. In the meantime, drillers are bemoaning the reliability of the system and desperately seeking alternatives, exploring the use of solar and natural gas to fuel power-generating gear on-site.

The electrical grid in West Texas “was not set up to withstand that much power going through it,” said Marco Caccavale, a vice president at the oilfield services company Baker Hughes. “Plain and simple, you have reliability challenges.”

Power is just one more oilfield complication in a region struggling to deal with extraordinary growth over an incredibly short period of time. Worker and pipeline shortages are major concerns, along with the growing levels of water and sand needed for fracking. Meanwhile, highways initially designed for minimal use are gridlocked in the day and deadly at night.

Conventional drilling with vertical wells in the region reached an apex in 1973, producing about 763 million barrels for the year. Output then steadily declined, falling to 309 million barrels in 2006. That threatened to turn a hot and dry region with few large communities back into a dusty afterthought requiring minimal electricity.

Then fracking hit.

The iconic 40-horsepower “nodding donkeys” that power vertical wells draw about 30 kilowatts each. But in the decade since the advent of fracking, the drilling technology that works to shake loose oil trapped in layers of shale, the old-style pumps are being supplanted by sophisticated equipment that needs more and more power to operate. At the same time, the well count has grown dramatically, rising by 33,483 since 2006, according to Austin-based Drilling Info Inc.

Shale wells developed using fracking can run horizontally for miles. To lift oil out, companies now depend on electric submersible pumps that individually draw about 300 kilowatts, according to Toni Jameson, an electrical-engineering consultant who leads a coalition of Permian companies studying the issue.

“Power is the last thing that anybody really ever thinks about,” Jameson said. “Most operators and producers out here, they’re here to produce. No one thinks about power until they realize, ‘We can’t produce that well without it.’”

One-Lane Road

The industry has studied the use of solar and wind at well sites, she said, but found the costs were high and that they couldn’t provide the power and consistency needed to run the new oilfield machinery. The Permian power grid is the equivalent of a one-lane country road, she said, adding, “we need about a 12-lane highway in both directions.”

The oilfield’s big-ticket items, drilling rigs and frack pumps, still mainly run on diesel engines, and aren’t affected by power outages. But for a well that’s moved past the drilling stage and into its longterm production phase, power is often the No. 1 operating cost.

Determined to find alternatives, the industry is experimenting with gear that can run off the natural gas produced in nearby wells. Gas-compressor sales in the region are up, which suggests more field gas is being processed locally to be used to generate power, James West, a New York-based analyst at Evercore ISI, said in an email.

Gas-Fired Turbine

Baker Hughes is working with several customers on a pilot project to power its electric submersible pumps from a gas-fired turbine, which can be more powerful than a diesel generator and requires less maintenance. The world’s second-biggest oilfield service provider sees its turbines filling a void in areas where the electrical grid hasn’t yet expanded, or where power cuts out too often.

The production process isn’t the only factor draining the region’s power, however. The ability to handle sand and water, vital ingredients in fracking, are also involved. It’s become a key factor in determining where to place pumps for moving water to the frack job, according to Bill Zartler, the chief executive officer of Solaris Midstream.

In some areas expensive generators have had to be used temporarily to run the pumps because there were no power lines to hook into, according to Zartler. In other spots, it’s been able to tap into customers’ electricity lines, he said.

There are solutions coming down the line.

Electrification Projects

Dave Stover, CEO at Noble Energy Inc., told analysts and investors in August the Houston-based explorer is working on an electrification project to solve that problem too. “Some of the supply of electricity is not that reliable in the southern Delaware Basin,” Stover said. “We’ve got some dollars going toward an electrification project that will help improve reliability there.”

Noble has a distribution system in place already, and anticipates constructing two substations near their wells in early 2019 to help relieve the load on the local distribution system.

Diamondback Energy Inc. is also in the process of building its own electrification project in Reeves County, estimating it will eventually cut costs by about $60,000 per well each month.

FlexGen Power Systems, a closely held provider of energy storage units in the Permian backed by the venture-capital firm Altira Group LLC, adapted its technology from the battlefields of Iraq and Afghanistan. The storage devices, which hold power generated in a variety of ways from the electric grid to diesel generators, guard against oil output downtime caused by outages.

“Power quality ends up being kind of a hidden menace,” said Flexgen CEO Josh Prueher, whose company last year signed a deal to work with Schlumberger Ltd. to help sell its storage units. “We do a lot of education of customers to show them that some of the production problems they’ve had actually were tied to power quality.”

Meanwhile, Oncor Electric Delivery Co. LLC, the biggest electric utility in the Permian, is spending $450 million to put new and upgraded transmission lines into the region by the end of 2021, according to Geoff Bailey, a company spokesman.

Oncor has seen its demand grow 79 percent in the oil patch over the past 12 months, with as much as 400 percent growth in certain spots in the basin over the past two to three years.

Oil explorers in the Permian “do a very good job of keeping their operations humming regardless of where the price of oil is at,” Bailey said. “We’re in regular contact with them to make sure we’re meeting their needs.”