Canada’s struggling oil industry is looking to what is known as partial upgrading technology to thin its sludge-like crude and squeeze more of it through congested pipelines.

It is the latest effort by the Alberta provincial government to rescue an industry hurt last year by steep discounts for its oil, as production far exceeded pipeline capacity. The government has already forced output cuts, given subsidies to petrochemical plants and said it would invest in trains to move crude.

Alberta in January announced a C$440 million loan guarantee for a C$2-billion partial upgrading facility planned by private company Value Creation. The Edmonton-area plant would turn 77,500 barrels per day (bpd) of diluted bitumen into medium crude oil and low-sulfur diesel, starting in 2022.

Producing a medium grade would give the world’s fourth-largest producer more of a different type of crude to sell that does not compete with abundant U.S. light shale oil.

Most of the oil produced in Canada is thick, heavy crude that comes from northern Alberta’s oil sands. Some is then put through a full upgrading process at great cost, turning that crude into synthetic light oil. Other heavy crude must be diluted with light oil – an extra expense – to travel through pipelines.

“Our crude oil would have a tailor fit to refineries, so we would have no problem to find the market,” Value Creation Chief Executive Columba Yeung said in an interview.

Partial upgrading is not yet done on a commercial scale anywhere. It removes sulfur and other impurities to create lighter grades of oil that do not require dilution to move through pipelines, lowering costs and making shipping more efficient.

In 2018, the United States imported 2.4 million barrels of medium, sour crude per day, only 15 percent of which came from Canada, according to IHS Markit. “There’s a case to be made for product diversification,” said IHS Vice President Kevin Birn.

The timing for partial upgrading comes with risks, however. Alberta’s New Democratic Party government is facing a tough spring election, and by the time the first upgrader is finished in 2022, additional pipeline capacity may be open, reducing the urgency to remove diluent from shipments to free up space.

The opposition United Conservative Party would review the viability of any subsidized energy projects if it forms a government, said Prasad Panda, the party’s energy critic.

Several pipelines in the works would raise Canada’s export capacity to 5.5 million bpd, creating a surplus of space until 2030, according to the Canadian Energy Research Institute. Yeung counters that additional pipelines would only enhance opportunities for partially upgraded oil to reach markets.

Developers of a dozen partial upgrading technologies, including MEG Energy Corp, are undeterred, however, and hope Value Creation’s plant is only the first.

Among the other companies grappling with ways to help alleviate Alberta’s problem is Calgary-based Fractal Systems, which intends to profit mainly by removing and reselling diluent from heavy crude.

Field Upgrading has a tiny 10 bpd pilot plant that it hopes to scale up to 10,000 bpd by 2022 to produce low-sulfur heavy oil suitable for marine shipping. The technology produces fuel compliant with tougher shipping emission requirements that take effect next year, said co-founder Neil Camarta.

“It’s really important that we get some of these technologies out of the lab and into development, because there’s potential there,” Camarta said.

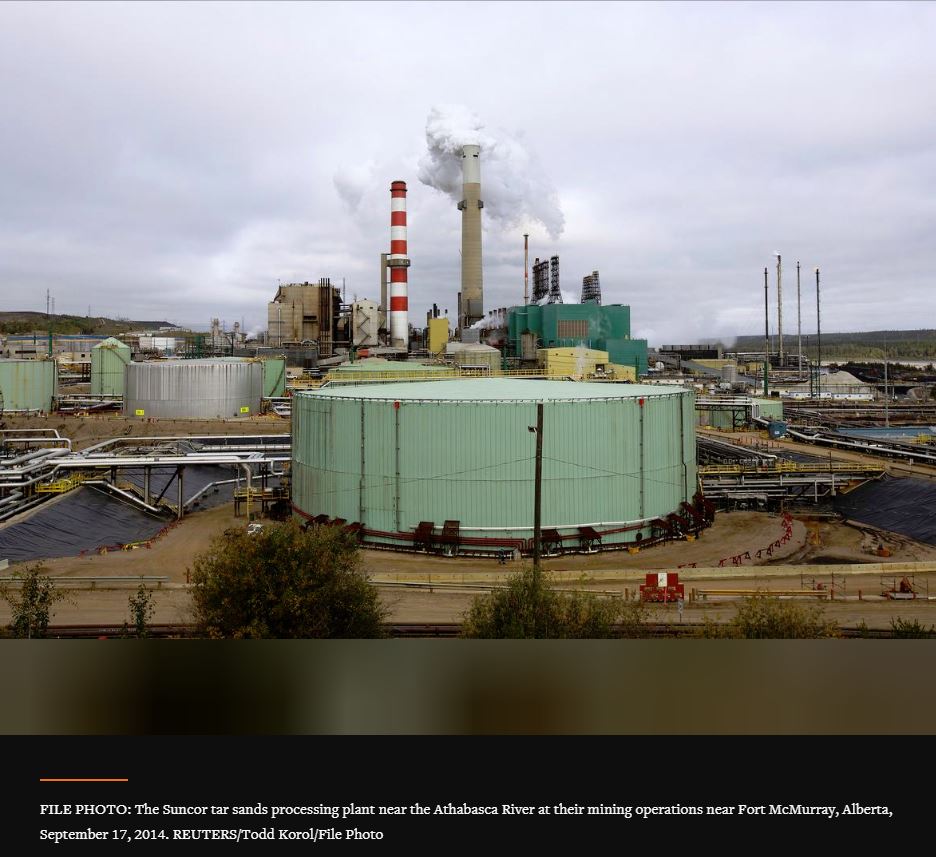

FILE PHOTO: The Suncor tar sands processing plant near the Athabasca River at their mining operations near Fort McMurray, Alberta, September 17, 2014. REUTERS/Todd Korol/File Photo