The U.S., now the world’s largest oil producer, is playing the role of disruptor in the global energy market.

Production has grown to a record 12.1 million barrels a day, eclipsing both Russia and Saudi Arabia in the past year. Exports have exceeded 3 million barrels a day, overtaking many OPEC nations. The implications are significant for both the U.S. and the oil market, which has seen huge price swings in just the past six months alone.

“Within the next two or three years, the U.S. will be a net exporter. By the end of the year, the U.S. will be producing 13 million barrels a day. This growth is a seismic event for the U.S. economy at this scale. U.S. oil production is 2.5 times what it was in 2008,” said Daniel Yergin, vice chairman of IHS Markit.

U.S. shale has posed a dilemma for OPEC as it has grown in spurts over the past decade, creating supply imbalances by pumping more when prices rise and cutting back as they drop. To battle the glut created by U.S. drillers, Russia formed an alliance with Saudi Arabia and the rest of the OPEC members, and together they have actively tried to either reduce or add supply to the market. But unlike those producers, U.S. production is driven by companies responding to market forces and that adds to the volatility in the world oil market.

“It’s really become such a huge story in terms of U.S. production, but also because of our policy. The U.S. is a swing producer but it’s also through policy that we’ve taken 1.6 million barrels off the market,” said Helima Croft, global head of commodities strategy at RBC. “We’ve been really lucky we’ve had the U.S. producers. That’s where the U.S. currently plays a role in helping out the market. Trump talks to the Saudis. Trump sanctions Venezuela. He’s really active in the market. Have we had a U.S. president be this consequential in the oil market, in terms of intervention?”

Trump’s policy has added to oil market volatility. When sanctions were announced on Iran last year, the U.S. said there would be no waivers for its customers. That sent oil prices higher. Yet, the U.S. did grant waivers to India and others during the fall, and that sent oil prices reeling. Iran exports are now about 1.1 million barrels a day, down from about 2.5 million in the spring. The waivers granted for those customers are up for review in May, so if they are not extended, more Iranian oil could come off the market.‘Going to be a market with tremendous volatility’

“It’s going to be a market with tremendous volatility,” said Carlos Pascual, IHS Markit senior vice president. “In 2018, the price of [Brent] oil went between $50 and $86 a barrel, but the average was $70. For the person looking at it and saying ‘$70, that’s not a big deal,’ depending on when you were buying, what country and what situation, the difference between $50 and $86 could be huge.”

About 4,000 representative of the global energy industry gather this week in Houston, where IHS Markit holds its annual CERAWeek conference. Oil CEOs from Chevron, BP, Hess, Occidental, and others will be in attendance. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Energy Secretary Rick Perry are expected to speak, as is OPEC Secretary General Mohammed Barkindo.

The U.S. has sanctioned Iran for its nuclear program and Venezuela for the human rights and other abuses by President Nicolas Maduro’s regime, which is supported by the military. Both countries are members of OPEC.

The U.S. and other nations have recognized opposition leader Juan Guaido, who declared himself president of Venezuela six weeks ago. The country’s oil production has been in decline, and some forecasts put the country’s production at just 500,000 barrels per day by the end of this year.

“We’re looking at a similar kind of [oil] market in 2018. A lot of volatility and an average that keeps us in a similar range of $70 a barrel. In that sense the sanctions on two OPEC members could potentially add to some of the uncertainty and volatility around that market,” Pascual said.

The Saudis have now committed to cut back to 9.8 million barrels a day, after sending close to 11 million barrels a day onto the market in the fall. As Saudi Arabia and Russia committed to cut production, oil prices began to rise again.

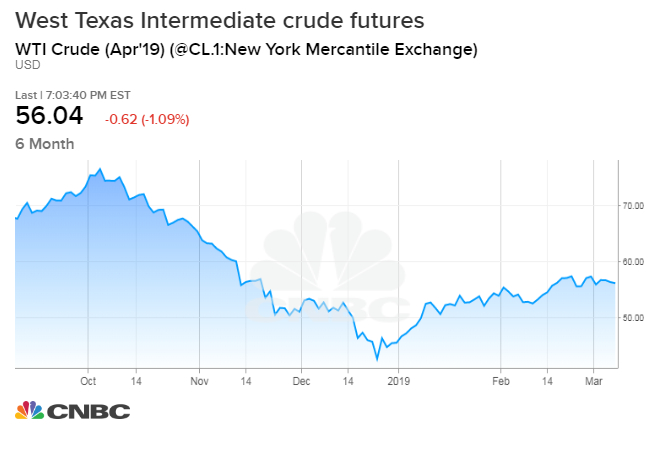

But Trump periodically presses OPEC about high prices in tweets. The price of West Texas Intermediate crude reached a high in the futures market of $57.88 per barrel this month, gaining 37 percent from its Dec. 24 low of $42.36. But that low came after a sharp 45 percent decline from the $76.90 it was at on Oct. 3.

“Trump seems to have picked up a fair amount of influence over OPEC and certainly the oil market has started to fear the Trump effect. Whenever he tweets prices shouldn’t go higher. The fear is the Saudis will follow and deliver, as they have so far. Shale will deliver if the Saudis don’t,” said Francisco Blanch, Bank of America Merrill Lynch head of global commodities and derivatives.

In the past week, Chevron and Exxon announced substantial increases in their production in the Permian Basin. Exxon said in a statement its production would be profitable in the Permian even if oil prices fell to $35 per barrel. The breakeven, or point where expenses for drilling a barrel of oil are covered, has fallen over the years for shale oil, and the major oil companies have helped drive it down even further, said John Kilduff of Again Capital.

“Saudi Arabia and Russia have a problem on their hands,” Kilduff said of the major oil companies’ shale production. “They’re running the risk of attempting to micromanage the price and blowing it on both ends, instead of staying steady. What happened to them in the fall was they got out there thinking there was going to be sanctions, and they ramped up production to respond to that.”

That plan backfired. “They got burned. Then you had Saudis go overboard and cut way back on exports to the U.S. and try to balance the market as rapidly as they could. Now they stand the chance of the price going higher than they want, which will only get more U.S. shale installed and produced,” Kilduff said.

The sanctions on Iran and Venezuela have removed some of the heavier crude from the market that is used by U.S. refineries on the Gulf Coast. The result is higher price differentials but Pascual said that could be temporary because of a new fuel requirement for the shipping industry, which uses a high sulfur sludge-like fuel.

“I think it’s a short-term story. The longer-term story is that after the IMO regulations come into place in January, which restricts the level of fuel that can be used in ships, then there’s going to be a drop in demand for heavy crude. It’s really a short term issue,” Pascual said.

Blanch said ultimately the oil market could become more like natural gas, a market with plenty of supply and less volatile prices than oil.

“I think over time volatility declines, and prices sit at the marginal cost of production,” he said. “The industry is going to have to decide if every marginal player has the right to exist, and some of those guys get rooted out. Consolidation is another likely trend. …That’s what’s going to happen in the next few years, and in the process you get ups and downs. You get Venezuelas and Irans.”

Photo as published in CNBC:

Ann Saphir | Reuters