Exactly when the world’s thirst for oil starts to ebb as a shift to cleaner, renewable energy gathers pace is increasingly occupying forecasters on both sides of the debate.

The booming growth of renewable energy and high hopes for electric cars are seen equally as a challenge or a panacea by the producers of fossil fuels and environmental groups alike.

Last month saw the dial appear to shift in favor of the latter, however, after BP became the first Western supermajor to pinpoint an inflection point in the world’s need for oil.

Tamed by a steady surge of wind and solar power, electric cars, more frugal vehicles and curbs on some plastics, Europe’s number two producer now sees oil demand peaking in the “late 2030”. A year ago it expected oil demand to rise beyond 2040.

The actual timing of the peak is less important than the direction of travel.

Updating its influential long-term Energy Outlook, BP’s less rosy outlook for oil demand speaks volumes to the growing concerns in many quarters that the world may be on a lot faster, and potentially more traumatic, path to energy transition than previously expected.

Until now, everyone in the oil industry— with the exception of Norway’s Statoil— expected oil demand to keep growing over the next two decades, albeit at a slowing pace.

Even the International Energy Agency still believes oil demand will continue to rise through 2040.

BP’s latest report shows how far oil companies have come in their public narrative as they face a world beyond oil.

Used as a benchmark for internal planning beyond just BP, the benchmark report also informs industry executives keen to grasp both the challenges and opportunities created by the rise of alternative fuels and renewable energy.

ExxonMobil, the industry’s biggest protagonist, has doggedly stuck to a more optimistic future for oil. ExxonMobil believes that demand for oil will likely continue to grow by 19% to 117 million b/d to 2040. BP sees it topping out at 110,000 b/d, up from about 97,000 b/d currently.

ON THE DEFENSE

A marked proliferation of future energy scenarios in BP’s outlook is also telling.

Eager to avoid even a reference to “base case”, or most likely scenario, BP offers no less than six different potential future trajectories for global energy, twice the number in its previous outlook.

In addition to considering a swifter shift to renewable energies and electric vehicles, BP even provides a ‘what-if’ scenario for a world where conventional, and even hybrid cars, are banned from 2040. Importantly, all but one of the scenarios—which assumes a slower rise of natural gas—are even more pessimistic on the future of oil demand.

As disruptive technologies such as electric cars and self-driving vehicles loom large, the future energy landscape becomes harder to predict. Key players, it seems, are hedging their bets much more than in the past.

Like the IEA, however, BP is keen to dispel the popular narrative that EVs will spell the collapse of world oil demand and send future oil prices plummeting. While more now optimistic on EV penetration rates, BP sees EV’s impact on demand in 2040 (some 4.5 million b/d) by far

outstripped by growth in demand for travel which is expected to double.

For its part, the IEA believes the call on peak oil is premature and the furore over the EV boom is creating a misinformed debate.

“Oil demand growth today is not driven by cars, it’s driven by trucks, planes, ships and the petrochemical industry,” the IEA’s executive

director Fatih Birol said in January. “Even if there was a big electrification of cars in the years to come, oil demand will still grow.”

Birol also points to the world’s poor track record since the 1980s on weaning itself off fossil fuels to decarbonize energy supplies.

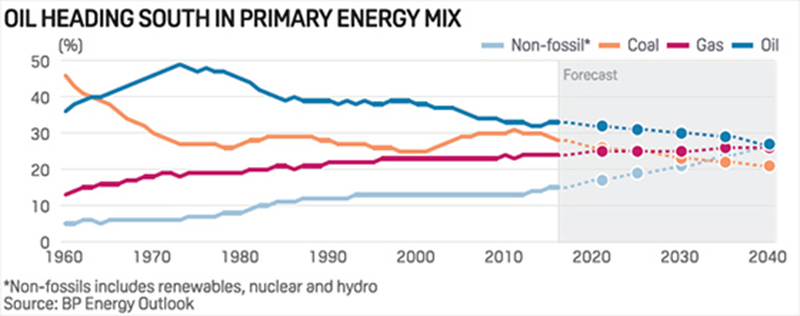

Over the last 30 years, he said, the share of fossil fuels has not fallen from 81%.

AN UNPREDICTABLE DEMISE

What now seems clear is that world’s track record on fossil fuels is about to change radically. Driven mainly by policy support in China and India, BP predicts renewable energy will grow five-fold over the next two decades, accounting for more than 40% of incremental energy supply. Combined with nuclear and hydro, non-fossil fuels combined are set to provide a quarter of the world’s energy in 2040.

The future story line for oil seems clear and one tied to that of world’s original fossil fuel coal; a slow but inexorable loss of share in the global energy mix from around a third today to a quarter in 2040 when renewables and gas take precedence.

With uncertainties over the impact of upstart technologies and global policy support for alternatives fuels and cleaner air, unpredictability over when peak oil arrives seem inevitable. But BP’s latest report shows just how fast the energy industry is having to recalibrate its expectations to fit a rapidly changing world.

Asked if BP has been surprised by the surging footprint of wind and solar power in recent years, the response of its chief economist Spencer Dale response was unequivocal.

“Massively,” he replied “…If you can find anybody who hasn’t been surprised, could you let me know?…Have we learned our lesson? I think so.”