In the previous article, I discussed the global nature of the oil markets. But the shale oil boom in the U.S. temporarily increased the localized impact on the West Texas Intermediate (WTI) benchmark. As a result, its price diverged from that of international crudes for a few years.

The natural gas markets, on the other hand, are far more localized due to the difficulty in transporting natural gas. That means that natural gas in the U.S. could be $3 per million British thermal units (MMBtu), but double or triple that level in Japan or Europe.

Natural gas production in the U.S. has exploded since the beginning of the shale gas boom. From 2005 to 2015, U.S. dry natural gas production increased by 50 percent. Natural gas prices fell in response. From 2005 to 2008, annualized natural gas prices hovered in a range from just under $7/MMBtu to nearly $9/MMBtu.

In 2009, the average annual price of natural gas fell below $5/MMBtu, and it has never been above that level on an annualized basis since then. On the other hand, the annualized price has been below $3/MMBtu in four of the past ten years.

But natural gas demand has been strong. Natural gas exports to Mexico have now exceeded 5 billion cubic feet per day (Bcf/d), equal to about 7 percent of U.S. daily production. Consumption by the electric power sector increased by nearly 50 percent from 2005 to 2016, reaching 27 Bcf/d. Industrial demand has also increased by 30 percent as some manufacturing relocated to the U.S. to take advantage of low gas prices.

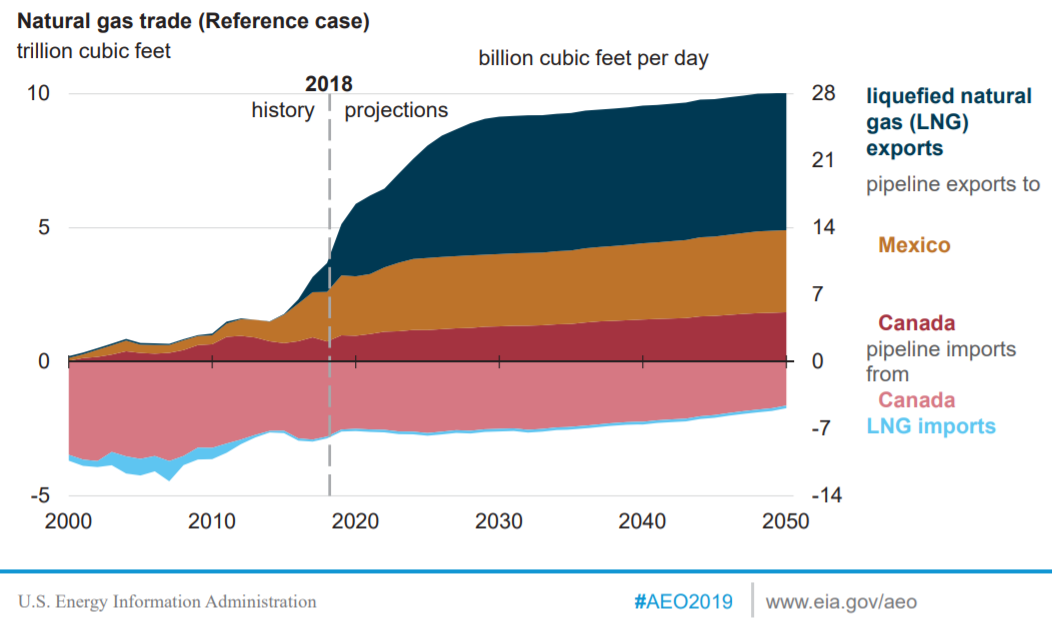

Demand has also increased from liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports. The Energy Information Administration recently announced that LNG exports reached 3.9 Bcf/d in December. But that’s a drop in the bucket compared to what is forecast.Related: U.S. Solar Industry Gains 150,000 Jobs In Eight Years

In its Annual Energy Outlook (AEO) 2019 with projections to 2050, the EIA projects a surge in LNG exports:

LNG exports will drive the natural gas trade.

This expected surge begs the question of whether U.S. natural gas supplies can continue to keep pace. I read an article earlier this week that correctly noted that to date, most of the U.S. natural gas production growth has been in the Appalachia Region. Appalachia production has exploded since 2009 from below 2 Bcf/d to more than 30 Bcf/d in 2018.

The EIA forecasts that the Appalachia will continue to produce 52 percent of cumulative production of U.S. shale gas through 2050. The article I read questioned whether Appalachia growth could continue its blistering pace, but it overlooked an important new source of U.S. natural gas.

The associated gas (co-produced with oil) in the Permian Basin is beginning to have a large impact on the natural gas market. There is so much gas being produced in the Permian that it has outstripped the pipeline capacity to get that gas to market. New pipelines are being built, but in the interim, there has been significant flaring and even natural gas prices falling below zero at times in the area.

Natural gas production in the Permian Basin has reached 13 Bcf/d, which is what the Appalachia Region produced in 2013. That reflects a doubling of production there in just over two years, and is now second only to the Appalachia Region’s 31 Bcf/d.

Further, Permian Basin gas production should continue to grow along with the region’s oil. A new assessment by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) estimated that there are 281 trillion cubic feet of undiscovered, technically recoverable natural gas in the Permian. That’s enough gas for 58 years of Permian production at 2018 rates.

So it looks the Appalachia Region and the Permian Basin will provide sufficient gas to feed the monster LNG demand growth that is forecast over the next decade.

The implication of this surge in LNG trade will be to make natural gas a more globally traded commodity. It won’t be quite as fungible as crude oil, but the impact should be to decrease some of the natural gas price disparity seen around the world.

U.S. natural gas prices should increase, while those in Asia and Europe should decline. The beneficiaries will be U.S. natural gas producers, global natural gas consumers, and the environment — as natural gas displaces coal in many Asian markets.

By Robert Rapier