The California Independent System Operator (CalISO), the entity tasked with managing roughly 80% of the California electricity grid, ordered rolling blackouts last Friday for the first time in 19 years. The finger-pointing began immediately, with various actors blaming renewables, problems at natural gas plants, the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC), and even market manipulators (the cause of the previous blackouts in 2001). No matter the underlying cause, however, the blackouts were ordered because of simple math: CalISO feared that supply was going to be unable to meet demand. The blackouts serve as an important reminder that for all the growth in renewables, natural gas is required in the near term to keep the grid stable and ensure resource adequacy.

CalISO operates multiple markets that utilizes real-time pricing, day-ahead resource bidding, and other mechanisms to dynamically match the ever-changing energy demand on the grid with available supply. This task is incredibly complex: demand on the grid from any one moment to the next is a guessing game, and CalISO must manage the dispatch of a variety of generating resources based on system demand, local demand, transmission line congestion, plant availability, wind conditions, sun and clouds, and more. It’s a minor miracle the system is as reliable as it is: nearly 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, a flip of a switch brings immediate light to a room (without any thought for the generating assets that somehow, somewhere, are ramping up to provide the grid with the extra few watts your lightbulb demands). The rolling blackouts hitting California now have impacted only a small portion of the state for a few hours each: 2 hours of lost time a year is still 99.98% reliability.

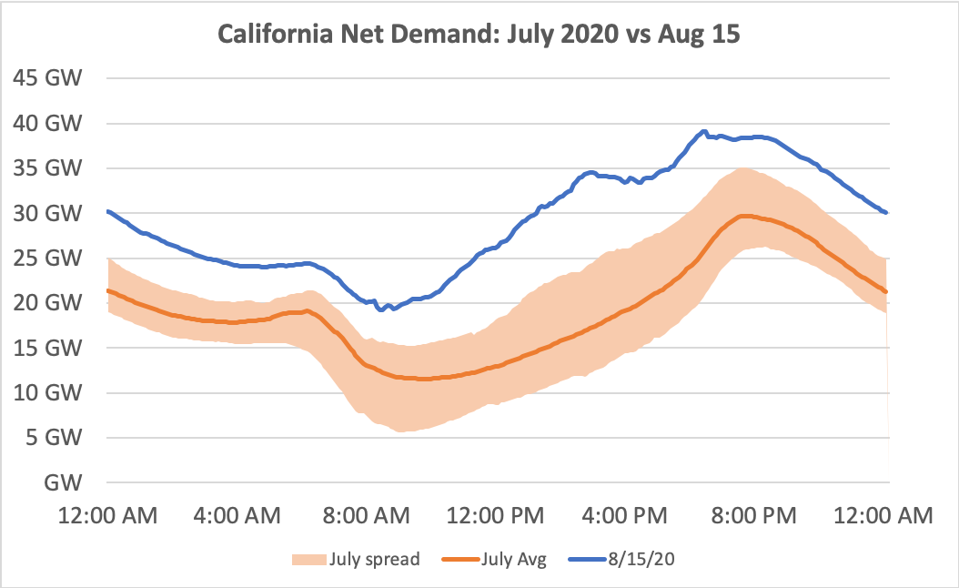

But for mission-critical systems where lives depend on performance, 99.98% doesn’t hit the mark. To ensure better reliability, the grid must be built to satisfy demand on the worst day of the year, while also maintaining further supply reserves in case a power plant unexpectedly goes offline or customers turn on more lights than expected. The plot below of “net demand” on the CalISO system, which represents the total demand minus non-dispatchable renewable sources, (aka solar and wind, which CalISO cannot get power from on-command), help illuminate the unique set of circumstances that caused such stress on the Califonia grid last week:

Net demand on August 15, the second day of blackouts, was multiple gigawatts higher than the maximum net demand seen in July. August 15 saw a double whammy hit the grid: total demand for electricity across CalISO was higher than any day in July, while renewables production was lower than any day in July. Taken together, net demand spiked, with its peak hitting (as it normally does) in the early evening as the sun was going down and solar assets across the state went offline. The increase in total electricity demand is typical for a heat wave, but this heat wave was abnormal for California and did not coincide with bright and sunny skies. Just as the heat wave hit, the remnants of a tropical storm system passed over the state, bringing humidity (further increasing air conditioning demand) and clouds (lowering solar production).

CalISO is usually prepared for even these tail events and uses a combination of natural gas power and imports from other states to meet days of high net demand. On August 15, CalISO called on over 25 GW of natural gas generation and 7 GW of imports at the net demand peak. The 7 GW of imported demand was in line with the July average, but the gas usage was nearly 10 GW higher than the normal day in July. CalISO would have imported more power if it was able, but the heat wave was widespread and other grids in nearby states had their own peaks to deal with.

Which brings us back to the importance of natural gas assets to ensuring grid stability. Reaching decarbonization goals requires replacing natural gas with something clean, but that means identifying and building out other dispatchable power sources. Energy imports are not the answer, as the events of August 15 show they are unreliable in geographically large heat events and are anyways self-defeating since those imports are likely fossil powered. Energy storage is the oft-proposed solution, but on August 15 renewables generated just shy of 150 GWh of electricity in California. Net demand for the day was 708 GWh, a gap of 558 GWh.

A renewable grid that would satisfy the demands of August 15 in California would require 4.7 times as much renewable generation capacity as is available today and sufficient energy storage to shift the extra daytime electrons from solar to the evening. This is where the largest challenge lies, as battery storage delivered just 6 GWh of energy on August 15, but there was just over 380 GWh of net demand between 7pm and 8am, when the sun doesn’t shine. If most of the renewables increase comes from solar deployments, that means a nearly 75-fold increase in storage capacity would be needed to satisfy the conditions seen on the 15th with a storage fleet that is 85% efficient. The equates to nearly $90 billion in capital expenditures, assuming batteries at $200/kWh (a generous assumption given today’s costs).

These numbers are rough, and there are undoubtedly other ways to firm the grid besides solar and storage, but they demonstrates the scale of the problem and the associated solution. California’s own plans, as articulated by the CPUC, add 74 GWh of renewables and 35 GWh of battery storage (see footnote for calculation assumptions) by 2030, with virtually no retirements of natural gas assets. The goals are well on the way towards a renewable grid, but fall far short of the requirements for 100% renewables. It’s clear natural gas is going to be part of the generating toolset for many years to come.

Read it from Forbes.com – Photo as seen on Forbes.com, “Natural gas plants will be part of the California energy supply for years to come. GETTY“