In mid-December with dwindling shopping days left before the holidays, North Dakota’s chief oil and natural gas regulator Lynn Helms was in a festive mood, reporting on his webinar for news media another set of new monthly production records in the Bakken Shale play.

In fact, for several years now, Helms has been holding these monthly press soirees because of continued robust growth in North Dakota’s portion of the Williston Basin. For this sparsely populated, resource-and grain-rich part of America, Helms is a bit of a rock star overseeing a golden cash cow for the governor and state legislature.

Helms

Helms is known for keeping close tabs on the sector as part of his position as head of the Department of Mineral Resources, which includes an oil and gas division, a role he has played in the state for nearly two decades. He saw the economic tidal wave known as the Bakken coming before it hit nearly 10 years ago. It has catapulted North Dakota to the No. 2 oil-producing state behind Texas, eclipsing historically oil-rich states such as Alaska and California.

Speaking almost casually, Helms in December was reporting the latest full monthly statistics covering October, and in that pre-winter time producers stepped on the accelerator ramping up oil production by 30,000 bpd, or 2.4%, and gas production jumped up, too, although not as much as oil, at 35 MMcf/d or 1.4%.

“Interestingly, we’re starting to see the gas-to-oil ratio coming into alignment,” he told reporters back then.

While Helms’ mood generally was upbeat in keeping with the pre-holiday production levels, he acknowledged that global prices and the latest corrective measures taken by OPEC and Russia were presenting mixed signals. He, therefore, was looking for Bakken producers to slow things down the first four or five months in 2019.

“OPEC’s announced 2 MMbpd cut should begin to rebalance the market,” Helms told the webinar audience. “There are a lot of mixed signals and the bulls and bears will duke it out in the global oil markets.”

Other, smaller but key entities, such as the Canadian province of Alberta (350,000 bpd cut) were also pursuing cutbacks in production at year-end 2018.

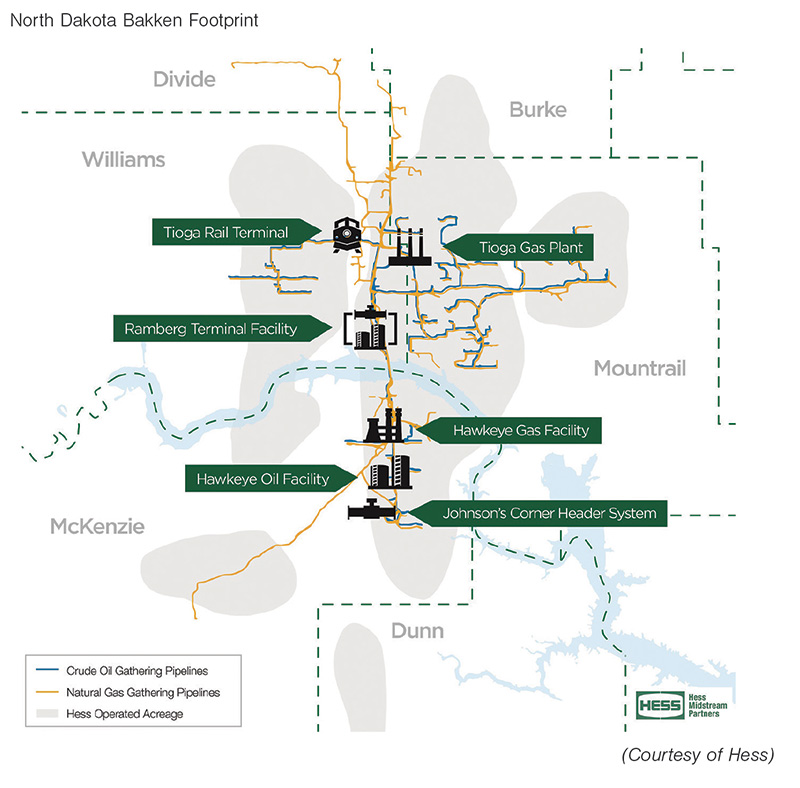

At about the same time at year-end 2018, one of the major Bakken operators, Hess Corp. and its CEO John Hess were touting the prospects for more cost-savings and expanded margins in 2019 and beyond, supported by an overall U.S. capital budget of nearly $2 billion for the new year. Hess intends to increase to six rigs in the Bakken, producing 135,000-145,000 boe/d.

In the Bakken, Hess plans to “complete the transition to higher intensity ‘plug-and-perf [perforation]’ completions in 2019, generating a significant uplift in net present value and initial production rates while also increasing the estimated ultimate recovery of oil and natural gas,” according to COO Greg Hill.

As the Hess’ were outlining their plans, Housley Carr, the respected energy analyst with RBN Energy LLC, published a commentary on his blog noting that while crude oil and natural gas production in the Bakken are at all-time highs, there is still bad news in that “for the past few months, the volumes of Bakken gas being flared are also at record levels, and producers as a whole have been exceeding the state of North Dakota’s goal” on the percentage of gas not captured, processed and piped away.

“At the end of 2018, state regulators stood by their flaring goals, but in an effort to ease the squeeze, they gave producers a lot more flexibility in what gas is counted – and not counted – when the flaring calculations are made,” Carr added in his blog:

“North Dakota crude production grew by 39% between January 2017 and September 2018 to an even 1.3 million bpd, according to the North Dakota Industrial Commission’s (NDIC) most recent numbers, and gas production was up an astonishing 62% over the same period, to about 2.53 Bcf/d. Those gains have put enormous pressure on the play’s infrastructure, and – of most interest to us in today’s blog – made it impossible for the state to meet its goals for reducing the percentage of produced gas that is flared.”

In early 2019, the three-member NDIC headed by the governor that oversees oil and gas regulation expects to receive a recommendation from the state’s Energy and Environmental Research Center (EERC) at the University of North Dakota on adopting gas storage programs to soak up for future use some of the gas volumes now being burned off.

Justin Kringstad, the numbers-crunching engineer who heads the North Dakota Pipeline Authority, was talking bullishly at year-end 2018 about the production prospects for oil and gas in the Bakken, underscoring this with indications that even the relatively small volumes from the Bakken in eastern Montana have been inching upward. And drilling activity was increased in the far western portions of North Dakota, near the Montana border. Where in mid-year there were zero rigs, Montana counted four rigs working at the end of 2018, Kringstad said.

“If you look across all fronts – oil, natural gas, natural gas liquids – every single area is going to have new pipeline investment in order to keep up with production,” Kringstad said. “There is not one segment of the industry right now that is prepared for long-term growth. The companies working these areas are busy in the boardrooms trying to figure out how many expanding existing systems are needed and how many are designed for open markets. So, for natural gas and all the fuels, there will be more infrastructures built.”

Besides regional production, Kringstad tracks rail and pipeline transportation, and for oil, the destinations of the cargo – West, East and Gulf Coasts. He also follows the changing spread between Brent (North Sea) and West Texas Intermediate (WTI) prices. If the difference is at least $5/bbl, rail is the favored transportation choice. At the end of 2018 with the Brent-WTI spread between $9 and $10, nearly three-quarters of the Bakken oil production was moving via pipeline with 16% going by rail, according to Kringstad.

While Kringstad and many other ongoing observer/participants in the Bakken dissect projections for a basin that some think contains billions of barrels of oil, they also pay attention to several other elements, including price, flaring of associated gas, workforce challenges and advances in technology and innovative processes.

Counties and subdivisions within the overall Williston Basin, which sprawls into neighboring states and across the international border into Canada, also need to be accounted for. Kringstad has tracked nine different ranges of break-even prices for Bakken production within the overall basin, ranging from as low as $26-$30/bbl up to highs of $58-$73/bbl.

Noting the global price decline at the end of 2018, John Harju, vice president for strategic partnerships at the university-based EERC, said he sees overall Bakken production continuing to move upward, but with the caveat that price is most likely to be the limiting factor – not resource base or technology – but the global commodity prices.

“I don’t think we have seen a dramatic pullback by our producers yet [in North Dakota], but it is always something to worry about,” Harju said. “Price is the big factor that we’re going to be challenged with. Our governor established 2 million bpd as a goal he has challenged the state to get to, and I don’t think that is a ceiling, it is an attainable goal, and like all of these things, everything is dependent on pricing.”

In its last quarterly conference call in 2018, the leading Bakken producer, Tulsa-based Continental Resources Corp., reported record third quarter production of 167,643 boe/d, with 42 completions averaging 2,013 boe/d. The company founded and still headed by billionaire CEO Harold Hamm had all of its top-10 initial production wells for a 30-day period in the past 12 months; they ranged in 30-day volumes from 2,603 boe/d to 1,784 boe/d.

Ron Ness, president of the North Dakota Petroleum Council (NDPC), notes that Kringstad’s estimates indicate the state is halfway to reaching a projected peak natural gas production volume of 5 Bcf/d.

“That would tell us we have a lot of work yet to do, and as oil/gas ratios decline, productivity increases,” Ness said. “There is a lot of continued investment that is going to be required. A lot depends on what happens with tertiary recovery. Can we re-inject gas effectively and that becomes a quasi-production storage enhancer? We know we have a lot more gas to come and a lot more infrastructure is needed. Hopefully it won’t require another $18 billion, but it seems like we’re going to need twice the gas processing capacity we have today if we’re going to get to 5 Bcf/d.”

With the prospect for a doubling of gas production in the years ahead, the issue of flaring becomes an ongoing challenge for the state and industry. As RBN Energy’s Carr recently noted “producers in western North Dakota have been struggling with gas capture and flaring issues for the better part of the last decade. Back in 2011 and again in 2014, as much as 37% of the produced gas was being flared due to a lack of processing and takeaway capacity.” It has been less than 20% in recent years, but it is still a major concern.

Under the new federal Bureau of Land Management (BLM) approach, the state will not be concerned with Native American reservation trust land wells and gas capture on the Fort Berthold Reservation in the Bakken. North Dakota will monitor the capture statistics on the non-trust lands.

“BLM is very much dedicated to delegating gas capture to the states,” Helms said. “We are meeting with them weekly with the goal of having a memorandum agreement in place by the first of February 2019. It will control the data transfer and establish how the state NDIC will notify the BLM.” Separately, the BLM and the tribes are working on an agreement for trust lands with the early February goal, too.

Whether they make that or not, the state will press on regarding the non-trust lands on the reservation, Helms said. “The huge BLM change for us is to delegate waste prevention to the states [federal fee lands] and tribes [on trust lands]. The BLM change is being challenged by environmental groups in California and New Mexico; but it nevertheless was effective in late November.”

Executives at one of the Bakken’s leading producers, Denver-based Whiting Petroleum Corp. in the last quarter of 2018 were telling Wall Street analysts that the company has a very high gas capture rate still, so it is somewhat apart from other operators.

“Many operators are in a different situation,” said Whiting CEO Brad Holly on an earnings conference call in late October. “We have been aware of the tightening gas situation for some time now, and we have been planning to put various strategies in place, so Whiting is well positioned.”

Harju

Flaring is the major challenge for operators and stakeholders alike in the Bakken, according to the EERC’s Harju, who is part of a team recommendation set for early 2019 on gas storage as a mitigating approach. He said that despite the hard work by his researchers and the industry, flaring volumes in 2018 were on the rise again.

“We’re just finishing up a study for the Industrial Commission to evaluate gas storage as an option to help mitigate flaring,” said Harju, adding that the advent of EOR is another possible outlet to attack flaring. “It would target either productive or nonproductive formations for the storage.

“One of our big challenges was not only the gas side of the equation, but also the export side. So, there is need for a lot of new pipelines, and NGLs are the really big challenge. The EERC has been working on the use of ethane and rich gas in general as a working fluid for EOR,” said Harju, noting the research center has a small pilot project ongoing in this regard with Liberty Resources. “If we’re able to get that to work in a meaningful way, that could be extremely helpful in terms of creating some substantial utilization, especially for the NGLs.”

Harju said in surveying the major Bakken producers in 2018, EOR came up as a leading area for research, and he calls it a “focal point” of the EERC research these days.

The petroleum council’s Ness equates flaring and related challenges to everything in the Bakken becoming what he calls “under-sized” going into 2019. But this also is creating opportunities and incentives for new investment, he thinks. Flaring will be a continuous challenge, he said because of infrastructure needs, market structure impacts, and “lots of other things.” Some of the other issues involve workforce needs for able-bodied workers with the right skill sets.

“What has happened is the production increases have been so phenomenal that the wells are so much more productive than they were a year ago,” said Ness, noting he is unsure how many billions of dollars more are needed in new investment. “So, everything again is under-sized, but it is a good opportunity, so where there is this type of incentive, there will be investment.”

Ness’s passion these days focuses on what the industry’s future will look like in terms of work force and its ability to keep stretching out to new frontiers in terms of technology and innovation. Ultimately, this is where the rubber meets the road for operators in North Dakota. And like the petroleum sector nationwide, there is a concern about where the next generation of workers will come from as the level of sophistication in jobs across the board is rising. Being located out of the mainstream of the nation’s oil patch and population, North Dakota feels this more acutely, according to stakeholders like Ness.

Ness said as long as there are other active oil and gas plays across the nation, North Dakota will always have a struggle for work force. As the state’s economy expands, the oil and gas sector is just one opportunity for new graduates and a 750,000 population cannot support all the workforce needs, he notes, adding that oil and gas workers generally come from the Upper Midwest (Minnesota, Wisconsin and Montana), Oregon, Wyoming and Texas.

“I think that is going to continue to be a challenge here,” said Ness, adding that current governor, Doug Burgum, has made oil and gas workforce issues one of his primary focal points. “We’ve got a lot of new students coming out of our schools, and we have to make sure that we create the opportunities for them, and the awareness of the jobs and the skilled training needed.”

One push back North Dakota has begun to enjoy against its relative geographic and demographic remoteness is that the Bakken has brought it worldwide recognition to a certain extent. Its operational and technological successes have caused energy practitioners around the world to take note, Ness said.

“I absolutely continue to be amazed at the advances in technology – not just the production side, but also on the environmental footprint,” he said.

Global interest includes the state’s use of unmanned aircraft (drones); remediation and reclamation practices; automation of well sites, and more, Ness thinks.

“It’s pretty enlightening, becoming the high-tech oilfield, there is no doubt,” said Ness. “North Dakota is really the official test site in the United States for drones right now. Drone activity here is very high.”

He said their use includes monitoring pipelines, monitoring facilities, reviewing reclamation sites and looking at easements.

From the EERC’s perspective, Harju said he is not that close to the work force issue, but he has seen a decline in engineering enrollments at the university, and at the same time he sees no lessening of advances in innovation and technology that will allow the oil and gas sector to do more each year without a huge increase in work force. The companies he works will are still “prudent, technologically oriented, agile and they have ‘continuous improvement’ cultures,” he said.

Noting that research assignments with the industry have never been as robust, Harju said when a group of operators in 2016 asked what the one area they needed to focus on was, he told them to “learn how to make money on $30/bbl oil,” and he thinks they took the advice to heart. “EERC research programs have grown through the latest price depression [2014-17], so these guys invested in research and the results are the successes we see today,” he said.

Harju sees more advances coming in the Bakken in terms of well completions, long 2- and 3-mile laterals, and re-fracturing work.

“There are a lot of older style hydraulic fracturing jobs that are being redone to bring a modern completion approach to them,” he said. “How you go about re-fracturing is absolutely ripe for innovation. Technology now evolves at a much faster pace, so I think we’re going to see a lot more in machine learning and artificial intelligence, so better understanding well completions is going to be a critical element.”

Helms’ ending to his December production webinar was the same upbeat stuff that Bakken followers are used to – record oil, gas production, and steady gas capture with much lower oil prices that so far had not translated into a drop-in rig count. “It has translated into more uncompleted wells and other items, so stay tuned,” the always positive Helms acknowledged.

At the outset of the new year, Helms focus had shifted to the EERC’s expected report on produced gas storage, for which he and the DMR engineers had been meeting with the research center.

Eyeing 2018 now in the rearview mirror, Helms called the EETC’s work “a very important report,” adding, “if the Industrial Commission goes along with the recommendations, North Dakota will be the first state to utilize this technology.”

In response to a reporter’s question, Helms said a lot of the operators who have missed gas capture targets in recent months are claiming force majeure or capacity constraints as his DMR department has been deluged with year-end notifications in this regard.

A sign of the times, perhaps, but it is not likely to dampen the enthusiasm of the Bakken faithful. P&GJ

Read it from PGJOnline

By Richard Nemec, Contributing Editor PGJOnline

Photo source: Hess