The oil industry tailspin created by a combination of glutted markets, weak demand and lingering apprehension over coronavirus shutdowns will lead to a wave of consolidation, energy experts agreed. And if history is a guide, megadeals may be on the horizon.

The biggest oil deals follow oil price crashes, according to an S&P Global Market Intelligence analysis of the past 25 years of M&A action in oil and gas. Since 1995, more than 50 deals have been completed in the sector valued over $10 billion. The priciest deals, excluding pipeline partnership reorganizations, all came after the market collapse in the late 1990s or the price fall that began in the second half of 2014.

Conditions are somewhat similar to the waning years of the 20th century that led to the demise of iconic companies such as Amoco, Mobil, Texaco, Phillips Petroleum and Atlantic Richfield as stand-alone entities, oil industry insiders and observers said. Although the fear of peak oil has receded, which creates less urgency for M&A, the industry is fragmented, profitability prospects are diminished, and the strongest companies have cash ready to spend.

“The current [West Texas Intermediate] oil seismic shock will likely serve as a catalyst for a new consolidation phase that is necessary to bring a fragmented [shale] industry into a more rational and sustainable level,” Goldman Sachs analysts wrote recently.

“There is no question” that production shut-ins and a collapse in U.S. drilling activity will produce enough pain that even financially strong shale companies will consider strategic mergers, said Rene Santos, senior director for exploration and production analysis at S&P Global Platts. “Everyone will be hurting, so it’s who’s hurting less, and are they willing to pick up someone else? And the answer is yes. I just don’t know how much.

“There will be some mergers, and you and I will be surprised — things that don’t make sense — but they go ahead and do it,” Santos said.

‘Scale game’ in shale

Consolidation, tighter financial conditions and rising barriers to entry typically lead to better returns in the oil industry, according to the Goldman analysts. Goldman’s analysis showed profitability improving for offshore and other long-cycle projects as those spaces have consolidated in recent years while shale has resisted consolidation.

Analysts and industry experts said the case for shale consolidation is straightforward. It allows producers to drill more efficiently by stitching together contiguous shale acreage and applying advanced analytics. It also cuts overhead costs and tames inflation as fewer companies compete for oilfield services and takeaway capacity. Leaner, more efficient companies would be better able to generate free cash flow and fund dividends and buybacks.

Former BP PLC CEO Lord John Browne, who sparked the buying spree just over two decades ago with a $53 billion acquisition of Amoco Corp., said he expects “significant restructuring” in the oil and natural gas sector, particularly among independents. Buyers will have the financial wherewithal to produce oil with their own finances to avoid debt traps caused by market volatility.

Shale production, with its constant need for new capital and rapid decline rates, may be more sustainable as part of a diversified portfolio that includes big, conventional projects with longer production lives and steady cash flow. Chevron Corp. Chairman and CEO Michael Wirth often said “the shale game has become a scale game” around the time his company attempted to buy Anadarko Petroleum for $33 billion in 2019. Wirth envisioned industrializing the shale process across 75 miles of combined Permian Basin acreage, funded by cash from interconnected Gulf of Mexico assets.

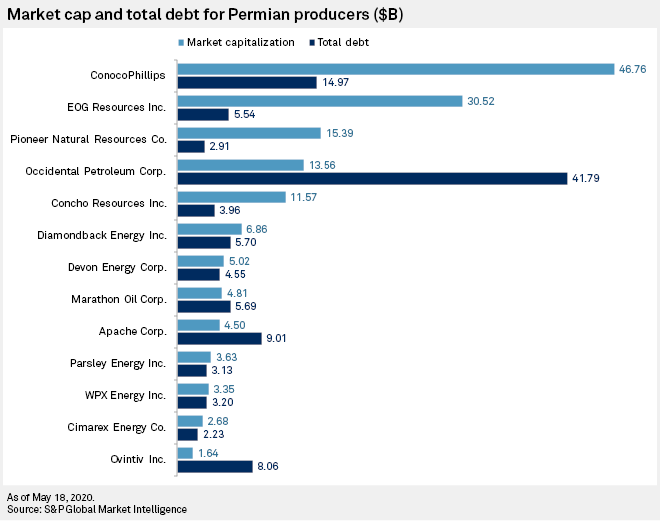

Yet when Anadarko instead selected Occidental Petroleum Corp.’s $57 billion offer, Chevron did not acquire another large Permian Basin producer, suggesting Wirth was being earnest when he said Anadarko presented a unique opportunity. The episode also illustrated the peril of large, leveraged shale buyouts. Occidental Petroleum has since engaged consultants to explore ways to digest its massive $40 billion debt load while also trying to sell roughly $15 billion of Anadarko assets.

New wave of bankruptcy coming

While waves of buying have historically followed oil price shocks, the scope of the most recent drops have put the global industry into uncharted territory. How much demand has been permanently destroyed by the COVID-19 pandemic and the ability of OPEC and non-OPEC producers to quickly ramp up production on positive price signals are factors that were absent in previous slumps. A decade of limited returns have also made bankers more cautious about lending based on the value of oil reserves.

The latest oil price plunge has prompted banks to reduce some producers’ borrowing base, credit often determined and secured by the value of oil and gas reserves. Production shut-ins and low prices have made it difficult for lenders to cut borrowing bases without triggering deficiencies and sending companies into a “death spiral” ending in bankruptcy, according to Buddy Clark, a partner at law firm Haynes and Boone and author of Oil Capital: The History of American Oil, Wildcatters, Independents and Their Bankers.

“We’re just in a new world, frankly,” Clark said. “A lot of questions that no one has ever had to answer before are being asked.”

During the bankruptcy cycle that accompanied the oil price crash in late 2014, equity holders got wiped out while bondholders swapped debt for equity and took control of the companies, often leaving management teams in place. The new equity holders resolved to hunker down and await the oil price recovery. Management teams were hesitant to trade their positions for equity stakes in combined companies and worried that Wall Street would not reward M&A.

This time around, experts expect fewer reorganizations through the Chapter 11 process and more Chapter 7 liquidations and asset sales through the 363 sale process in bankruptcy, ultimately leading to fewer operators.

“What we’re already seeing is unsecured bondholders are as deep underwater as equity is, and the second liens are under water,” Clark said. “First-lien secured banks are going to be impaired on a number of these filings. Those banks are not at all interested in becoming oil and gas companies or amassing a bunch of oil and gas assets.”

However, many of the companies that will file for bankruptcy do not have optimal acreage, and majors tend to be most interested in Tier 1 assets controlled by larger, healthier companies, said Andrew Dittmar, senior M&A analyst at energy data and analytics firm Enverus. Acquiring assets from small bankrupt players will chiefly drive sub-billion-dollar deals that will not yield meaningful consolidation, in Dittmar’s view. Larger companies such as Whiting Petroleum Corp. or Chapter 11 candidate Chesapeake Energy Corp. could present more significant opportunities for consolidation if they emerge from bankruptcy with clean balance sheets.

However, M&A usually does not pick up until potential acquirers see signs of improvement in commodity markets, Dittmar said. If companies still look cheap and investors remain dissatisfied with shale stock returns as oil prices stabilize, deals could start falling into place, the analyst said.

“The environment we’re in has some of the pieces in place, but what we’re probably really missing is some sort of sign of hope on oil prices,” Dittmar said. “Before everything washes out, we’ll have fewer players than we do today. It’s just that how those combinations are going to fit together, and what the timing of the next few years is going to be, is really difficult to call.”

‘Discounted gems’ missing

While equity markets have been pummeled in recent months, oil and gas company shares have generally recovered ahead of commodity prices, diminishing the ability of investors or acquirers to pick up “discounted gems,” said Judith Dwarkin, senior economist at RS Energy Group in Calgary, Alberta.

“Both the prospects for long-term oil demand growth and the complexion of non-OPEC supply are very different today versus then,” Dwarkin said. “Investor confidence in the sector has been shaken up by increasingly unpredictable OPEC policy decisions. The path to recovery in nearer-term oil demand is extremely uncertain.”

ConocoPhillips is on the lookout for acquisitions, but deals must contribute to growth and cannot destroy the company’s financial framework, Chairman and CEO Ryan Lance told CNBC in April. “Certainly this situation has caused a lot of distress in our industry, but it is in need of consolidation. There’s too much fixed cost. Investors have too many choices. Your market cap’s not relevant anymore.”

Long-time Exxon Mobil Corp. executive Brad Corson, now CEO of the company’s biggest Canadian subsidiary, Imperial Oil Ltd., said the integrated oil sands producer is keeping an “aperture open” for potential takeover targets. Corson took the reins at Imperial in September 2019 after 38 years at Exxon, including his most recent stint as president of the Texas-based oil giant’s upstream ventures unit, where he was responsible for global acquisition and divestment programs. The current dip in commodities prices has led to an abundance of distressed assets, but that does not mean a deal would be easy to complete, Corson said on a May 1 conference call.

“My experience in M&A is that at these extreme points in the cycle, it could be very difficult to transact because buyers’ and sellers’ expectations become very different, and the view of what recovery might look like, and the timing for that, is often very different,” Corson said. “So it’s difficult to transact, but that doesn’t discourage us from continuing to evaluate potential opportunities and see if there is something that makes good strategic sense for us.”

Imperial is the type of company that could be in the next big deal; it has a significant cash war chest and it could be motivated by new oil sands takeaway capacity, said Phil Skolnick, managing director of equity research at Eight Capital in New York. “Imperial had over [C]$1.7 billion of cash on hand at year-end 2019,” Skolnick said. “One could believe that MEG Energy Corp. and/or Cenovus Energy Inc. likely look even more appealing to Imperial, in our view, given now that there is clarity around a major egress add in 2023.”

As the world returns to normal after COVID-19, oil companies may need to decide if increasing their output of hydrocarbons is something their investors will reward or if they should concentrate on improving their environmental, social and governance approaches to appeal to shareholders, former BP boss Browne said.

Consolidation in oil production may be something better left to state-owned companies and funds. “I expect [the big companies] look at oil in particular and oil products and say to themselves, ‘Maybe this is an area where I won’t actually be able to grow,'” Browne said. “‘I might just extract some cash, and I’ll let the state companies who, after all, produce most of the oil in the world, take on that business.'”

S&P Global Platts and S&P Global Market Intelligence are owned by S&P Global Inc.

Read it from SPGlobal – Photo as poste on SPGlobal